Kate Daw: The Blue Hour

Things we know we know

I am writing this with pen and paper and it's already strange to me. There was a time when I wondered if I would ever be able to write on a computer because I hand-wrote almost everything longer than an email. And then I transcribed it. Now, years later, it is the other way around. Some things change. . .

It's about Kate Daw's artwork. With Kate's work some things change and some things remain the same-often at the same time. Her use of typed canvases is well known; the format has stayed the same but the content continues to change (recipes, quotes from novels). Her fascination with food, café's and crockery has persisted but her media, form and dealings with these epicurean artefacts have changed significantly. Sometimes Kate plucks a design motif from the real world and paints it. It might be a particular fabric print or a ceramic dinnerware design. When she does this I can't help but think of Jasper Johns' Beer Cans (1960): now you see them, now you see them again (but this time a little bit different).

I wonder why she does this?

I am of the opinion that Kate believes in these artefacts for various reasons. One is that they are signifiers for her. Each little decision to include an object is meaningful. She is able to construct a world around these signifiers as if to reflect a personality. Probably her personality. With a bit of modular personae thrown in. In this sense she is a romantic but although many of her sources come from different periods of time, I am not convinced that Kate is a nostalgic. Through her process and list making, she brings forth qualitative aspects of these source-times to the now. Fragments and traces of lives are drawn and inhabited again and this time around the artist participates in the shaping. This new registration has the ability to elide mundane laws of construction. Romanticism is her challenge to rationality.

It's not just about Kate though because I recognise many of her mnemonics. Acapulco kills me. The word work and the image work. Kate's works are known knowns. I know what she means and yet I don't know exactly what she means. There was a time when Acapulco was a hip holiday resort and, given this, I could run off a slew of associations with that word (water-skiing!!) but I shouldn't do it now because that's the viewer's task. The source for the image Acapulco, however, is a chic, Mexican folk influenced, dinnerware pattern, designed by Christine Reuter for Villeroy and Boch in 1967. Kate has painted a version of it and then silk-screened her painting. The doppelgänger effect of this repetition is subtle and strange and somehow it charges the image with a further energy. What was originally a bold print of primary colours has now revealed a ghosting quality in its double register as it completes a circular path to its repeated printed output.

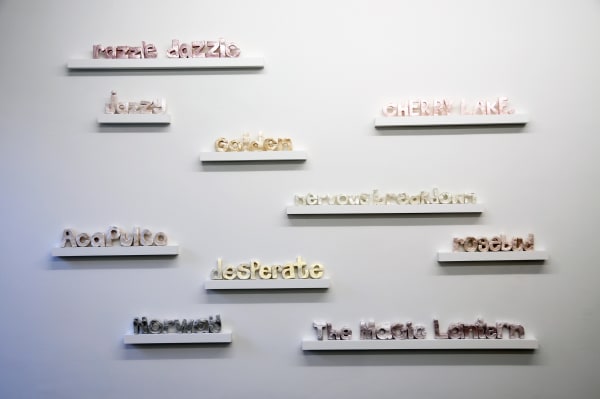

Her ceramic singsongs are like baked almond biscuits coated with pearlescent icing. This assembly of words seem indiscriminate and heterogeneous: place names, movie trivia, glitzy adjectives, but nevertheless they are collected, stacked and polished. It is as if Kate has been picking her linguistic flowers at the side of the road and has taken them back to the studio for contemplation. To quote Lewis Hyde, 'we poeticise as transients' and of course the bluebells are different from the agapanthus but her posy is the microcosm of the 'uncontained inexhaustible world.'*

The title of the exhibition is The Blue Hour. This term describes the transitional time from daylight to dark or dark to daylight. It is the liminal time beginning just before sunset when light and dark even out. The gloaming. It is also cocktail time, when business comes to a close at 5pm and the practicalities of the day are done. The hour when it is permitted to take a drink, meet with friends and leisurely allow a freer world to flow in; sensible shoes can be discarded and little black dresses and fascinators can be donned. Sex in the City. A time when blondes look their best in the blue evening light and those roadside flowers are at their most fragrant.

John Meade

* Trickster Makes this World, (1998) by Lewis Hyde.