Kate Daw: In Between Days

pop songs do it better

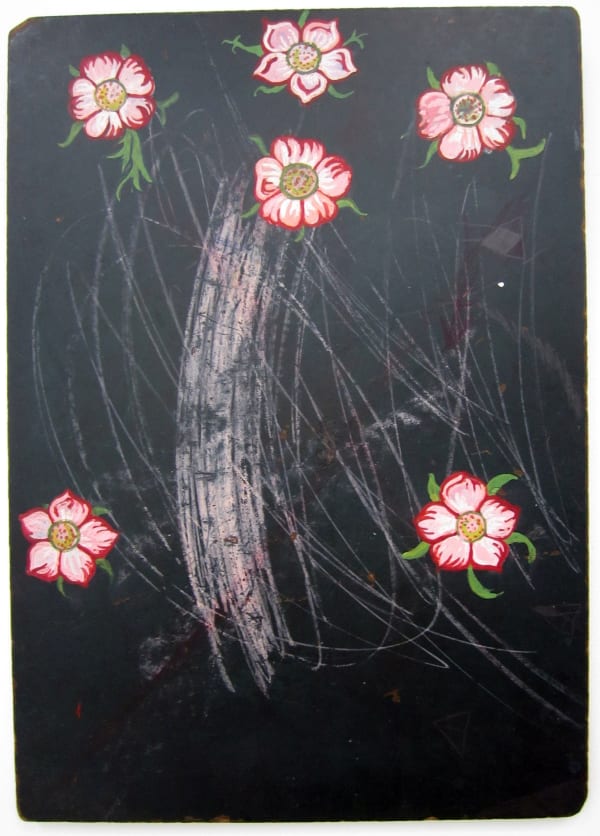

I walked into Kate’s house and noticed the artwork pop songs do it better in the hallway, as usual. It’s by Janice McNab. Kate and Janice used to show work together and on this day it reminded me of the first time I came across Kate’s work at the Collective Gallery on Cockburn Street in Edinburgh, which must have been 1997 or 98.

In 2000 I’d just relocated from London to Australia and my first project was an invitation to work with the recently rediscovered Florence Broadhurst collection. It’s a familiar story now, but just to refresh – late in life, Broadhurst established a studio making wallpaper and became a prodigious producer of popular designs. She was a complex, eccentric woman who created and presented many identities and lived an extraordinary life, which ended tragically when she was brutally murdered in her Sydney showroom. I was introduced to Broadhurst through a vast collection of film and hand drawn positives set out in repeat, side-to-side and top-to-bottom for screen printing wallpaper. In amongst the positives from Broadhurst’s studio there were others from the same era. The only way I could tell which were the Broadhurst designs was by looking for the name. I remember selecting a set of the Broadhursts and pinning up photocopies at actual size to imagine the impact they would have in a room. It was quite extreme for our sedate contemporary domestic interiors, but I remember being struck by how very familiar this collection was, maybe a childhood memory.

Two hundred and fifty years ago our first wave of British colonisers found themselves geographically isolated and potentially free from the rigorous moral absolutes of early 19th century Britain. In 1851, Victoria separated from New South Wales and, in England, the influential designer, writer and libertarian socialist William Morris famously described the entire contents of the Great Exhibition as ‘tonnes upon tonnes of unutterable rubbish’. In 1862, Morris created his first repeating design for textiles. In 1896, in rural England, William Morris died and in 1899, in rural Queensland, Florence Broadhurst was born. To me, the Broadhurst collection had no obvious designer fingerprint. I was getting excited because this felt like the type of collection you could learn something from – prolific and led by the subtle changes in taste that is the high street. For an artist with an interest in social anthropology, this is the stuff. But the prize is pretty inaccessible, buried deep, with no help from google critiques. This work is made on the fly responding to the vagaries of us, the masses.

When Florence returned to Australia from an extended stay in England in 1949, she was still toying with her own identity. She had ditched her beginnings in rural Queensland and managed to successfully pass herself off as an English woman, even hinting at an aristocratic lineage. This persona was so well established that, in 1977, her obituaries announced the untimely death of English wallpaper designer Florence Broadhurst. The designs in her collection were obviously derivative and that’s me being kind. There was no sense of a need to disguise the design source either, no 10% difference needed then. There were a couple of cross hatch copies of two William Morris designs boldly entitled William and Morris and there’s an Aubrey Beardsley drawing in repeat called Aubrey.

I think it was Tacita Dean who said one of the roles of contemporary artists was as custodian of redundant technology ... something like that.

I was watching TV – a team of scientists bored holes in the bottom of a lake, and later they used the cylinders of collected stratified silt to explain periods of environmental turbulence and change. A series of banded colour revealed a reversal of the magnetic poles, followed by a band of uninterrupted grey describing a period of stability.

Broadhurst was a follower in design terms, not an originator, and that’s what makes this kind of popular collection potentially such an invaluable resource. Her starting point was to introduce a British look to an Australian market at just the time the demography of Australia was beginning a period of rapid change. Early designs cite exclusively European flora and fauna, then the work shifts to encompass classical and Mediterranean themes; Asian influences follow and, finally, by osmosis, indigenous flora joins the European varieties. I remember going to London to show the designs to Rupert Thomas at World of Interiors. I was a bit nervous, thought he might throw me out, but it soon became clear he was fascinated and clearly loving it. Their origins were well known to him, but the limitations of the process, the practical parameters of Broadhurst’s production made them ‘lighter’ and just a little bit foreign to a European eye.

I left Kate in her studio with William Morris and Florence Broadhurst as companions – a collector deep in the murky waters of repeat design, generic florals and the high street. On my way down towards her front door I stopped in front of pop songs do it better and felt sure William Morris would be on our side. As for Florence – I imagine she’d be looking for the commercial angle, perhaps they could’ve been quite a team.

Stewart Russell, October 2011